This is the appendix to the article, “Getting to the Root of the Root Canal Controversy.”

Table of Contents

Toxic Tooth Preface.

It’s Time to Break Down the Wall Between Dentistry and Medicine. By Bruce Donoff MD, DDS (Stat news 2017)

Dental Caries and Head and Neck Cancer (JAMA, 2013)

AAE Newsletters

Jerry Bouquot, DDS, MSD Biographical Profile

Patient Letters to the NYS Dental Board

Weston Price Bio

Articles by Easlick and Grossman that are referenced by the AAE that they say debunks Focal Infection Theory. Current peer reviewed research shows that these articles are filled with false assumptions and outdated information.

Article about Dr. Oz article in response to his critics.

Article: Yes, Licensing Boards Are Cartels. The Case For Why Congress Should Get Involved. By Eric Boehm. Sept. 2017).

Article: The Truth About Dentistry. It’s Much Less Scientific-And More Prone to Gratuitous Procedures-Than You may Think. By Ferris Jabr. The Atlantic. May, 2019).

Article: Root Canal Safety. By Dr. Marcus Johnson. This article is endorsed by the AAE.

More on Stephen Barrett, Jackson Leeds and others.

Appendix

Appendix A: Toxic Tooth Preface

Appendix B:

The belief that oral health is an integral part of total health is gaining momentum. Bruce Donoff, D.M.D.M.D., professor of oral and maxillofacial surgery and dean of the Harvard School of Dental Medicine writes:

“Ever since the first dental school was founded in the United States in 1840, dentistry and medicine have been taught as — and viewed as — two separate professions. That artificial division is bad for the public’s health. It’s time to bring the mouth back into the body. As taught in most schools today, dental education produces good clinicians who have a solid understanding of oral health, but often a more limited perspective on overall health. Few dental students are equipped to take a holistic view that may include taking a patient’s vital signs, evaluating their risk of heart disease or stroke, spotting early warning signs of disease…

My school, the Harvard School of Dental Medicine, was founded 150 years ago on July 17, 1867. It was the first American dental school affiliated with a university and its medical school, and the first to grant the doctor of dental medicine (D.M.D.) degree. The school’s mission is “to develop and foster a community of global leaders dedicated to improving human health by integrating dentistry and medicine at the forefront of education, research, and patient care.” At commencement, dental graduates are welcomed into a “demanding branch of medicine.”…

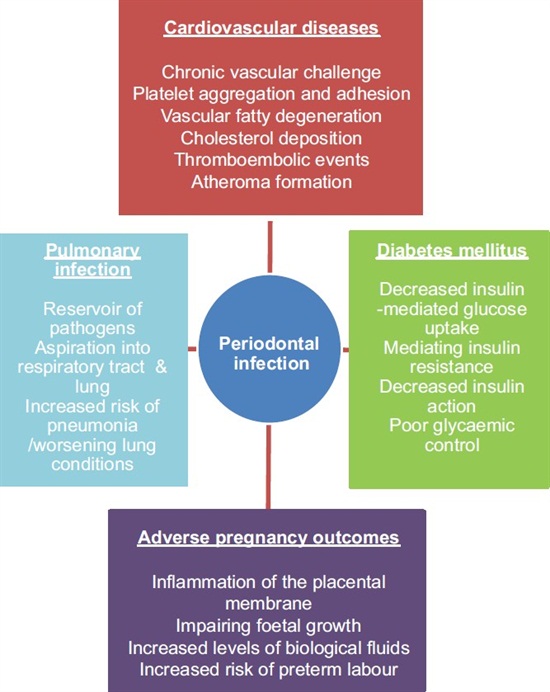

Poor oral health is more than a “tooth problem.” We use our mouth to eat, to breathe, and to speak. Oral pain results in lost time from school and work and lowered self-esteem. Inflammation in the gums and mouth may help set the stage for diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and other chronic conditions. Dental infection can lead to the potentially serious blood infection known as sepsis. In the case of 12-year-old Deamonte Driver, an infected tooth led to a fatal brain infection.

Writing in the Millbank Quarterly, John McDonough, professor of public health practice at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health asked, “Might oral health be the next big thing?” I believe that it needs to be — and should be.”

The school has also established the Oral Physician Program, a general practice dental residency program at the Cambridge Health Alliance, which integrates oral health, primary care, and family medicine training. We also plan to establish a new combined DMD/MD program with a hospital-based residency to train a new type of physician focused equally on oral health and primary care.

Other institutions are also expanding the concept of dental care and chipping away at the barriers between dental care and primary care. Kaiser Permanente Northwest, for example, has opened a truly integrated medical-dental practice in Eugene, Ore. The Marshfield Clinic in Wisconsin is advancing the concept with integrated medical-dental electronic health records.

Here’s what an integrated dental health/primary care visit might look like to a patient: When you go for a routine teeth cleaning, you would be cared for by a team of physicians, dentists, nurses, and physician and dental assistants. One or more of them would take your blood pressure, check your weight, update your medications, see if you are due for any preventive screenings or treatments, and clean your teeth. If you have an artificial heart valve or have previously had a heart infection, or you are taking a blood thinner, your clinicians will manage these conditions without multiple calls to referring doctors.

Finding the political will to integrate dentistry and primary care is a challenge. Various organizations including the DentaQuest Foundation, the Santa Fe Group, and Oral Health America have taken up the task. The majority of this work is designed to raise awareness of oral health, educate non-dental health care providers, and create political interest in promoting oral health. However, while interprofessional education has met with some success, interprofessional practice remains elusive.

The culture of the dental profession must change to promote closer connections between dentistry and primary care. …

In 2000, the surgeon general’s report “Oral Health in America” drew attention to the gap in oral health in the U.S. In a 2016 update, then-Surgeon General Vivek Murthy strongly recommended integrating oral health and primary care. Closer collaboration between dentistry and primary care could change the culture of health care, close the access gap, and improve general health by providing primary care services during dental visits. It could also improve population health and chronic disease care.

We cannot drill, fill, and extract our way to better oral and overall health. We need a fundamentally different approach, one that accentuates disease prevention and health management using a multidisciplinary, integrated, and patient-centric approach to overall health. And that means breaking down the wall between dentistry and medicine. [Statnews. 2017]

Appendix C:

October 2013

Dental Caries and Head and Neck Cancers

Mine Tezal, DDS, PhD1; Frank A. Scannapieco, DMD, PhD1; Jean Wactawski-Wende, PhD2; et alJukka H. Meurman, MD, PhD3; James R. Marshall, PhD4; Isolde Gina Rojas, DDS, PhD5; Daniel L. Stoler, PhD6; Robert J. Genco, DDS, PhD1

Author Affiliations Article Information

JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139(10):1054-1060. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2013.4569

Abstract

Importance Dental caries is the demineralization of tooth structures by lactic acid from fermentation of carbohydrates by commensal gram-positive bacteria. Cariogenic bacteria have been shown to elicit a potent Th1 cytokine polarization and a cell-mediated immune response.

Objective To test the association between dental caries and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC).

Design, Setting, and Participants Case-control study in a comprehensive cancer center including all patients with newly diagnosed primary HNSCC between 1999 and 2007 as cases and all patients without a cancer diagnosis as controls. Those with a history of cancer, dysplasia, or immunodeficiency or who were younger than 21 years were excluded.

Exposures Dental caries, fillings, crowns, and endodontic treatments, measured by the number of affected teeth; missing teeth. We also computed an index variable: decayed, missing, and filled teeth (DMFT).

Main Outcomes and Measures Incident HNSCC.

Results We included 620 participants (399 cases and 221 controls). Cases had a significantly lower mean (SD) number of teeth with caries (1.58 [2.52] vs 2.04 [2.15]; P = .03), crowns (1.27 [2.65] vs 2.10 [3.57]; P = .01), endodontic treatments (0.56 [1.24] vs 1.01 [2.04]; P = .01), and fillings (5.39 [4.31] vs 6.17 [4.51]; P = .04) but more missing teeth (13.71 [10.27] vs 8.50 [8.32]; P < .001) than controls. There was no significant difference in mean DMFT. After adjustment for age at diagnosis, sex, marital status, smoking status, and alcohol use, those in the upper tertiles of caries (odds ratio [OR], 0.32 [95% CI, 0.19-0.55]; P for trend = .001), crowns (OR, 0.46 [95% CI, 0.26-0.84]; P for trend = .03), and endodontic treatments (OR, 0.55 [95% CI, 0.30-1.01]; P for trend = .15) were less likely to have HNSCC than those in the lower tertiles. Missing teeth was no longer associated with HNSCC after adjustment for confounding.

Conclusions and Relevance There is an inverse association between HNSCC and dental caries. This study provides insights for future studies to assess potential beneficial effects of lactic acid bacteria and the associated immune response on HNSCC.

The American Cancer Society predicted an estimated 53 640 new cases of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) and 11 520 deaths in 2013 in the United States.1 A steady increase in the incidence of oropharyngeal cancers has been observed over the past 3 decades despite a substantial decline in tobacco consumption.2 This increase has been attributed mainly to oral infection with human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16, which was shown to be a causal factor.2 Whereas bacterial colonizations on oral mucosa also differ between healthy individuals and patients with cancer, a causal association between an oral bacterial infection and HNSCC has not been established.3

Dental caries (or decay) and periodontitis are major oral bacterial infections associated with dental plaque.4,5 Although these 2 oral diseases are often combined in a single category as indicators of poor oral health, they are distinct in terms of both etiology and outcome. Periodontitis is a chronic inflammation of structures around the teeth associated with gram-negative anaerobic bacteria leading to alveolar bone loss (ABL).5 It is characterized by Th2 and Th17 polarized immune responses.5In contrast, dental caries results from demineralization of teeth by lactic acid produced from the fermentation of carbohydrates by gram-positive facultative bacteria.4 Cariogenic bacteria are associated with periodontal health, and decreased levels of these commensal bacteria have been shown to be associated with increased periodontal inflammation and destruction.6-8 Multiple studies have shown that dental caries and associated bacteria elicit a potent Th1 immune response in peripheral blood mononuclear cells promoting CD8+ T-cell response.9-11 Whereas Th2 and Th17 cell responses have been generally associated with increased risk of cancer, Th1 cell response has been consistently associated with decreased risk of cancer.12

We previously observed that periodontitis was associated with increased risk of oral potentially malignant disorders13 and HNSCC.14 The purpose of the present study was to test the association between dental caries and HNSCC.

Methods

Study Design and Population

We conducted a case-control study of newly presenting patients of the Department of Dentistry and Maxillofacial Prosthetics at Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI). All patients seen between June 15, 1999, and September 14, 2007, except those who had a history of cancer, dysplasia, or immunodeficiency or were younger than 21 years were included. The RPCI patients come mainly from the surrounding Erie, Niagara, and Chautauqua counties and have a wide range of socioeconomic status. This study was reviewed and approved by institutional review boards of the RPCI and the State University of New York at Buffalo.

Cases

All patients with newly diagnosed primary HNSCC during the study period who met the inclusion criteria were included as cases. The following sites, identified from the RPCI Tumor Registry according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition,15 were included: oral cavity, including oral tongue (C02.0-C02.9), gum (C03.0-C03.9), floor of the mouth (C04.0-C04.9), hard palate (C05.0), buccal mucosa (C06.0), vestibule (C06.1), retromolar area (C06.2), and other parts of the mouth (C06.8-C06.9); oropharynx, including base of tongue (C01.0), soft palate (C05.1), tonsil (C09.0-C09.9), and oropharynx (C10.0-C10.9); and larynx (C32.0-C32.9).

Controls

All new patients seen at the department during the same time period as the cases but who did not have a diagnosis of cancer or dysplasia and met the inclusion criteria were included as controls. These included general dentistry patients, as well as those with a diagnosis of benign mucosal lesions such as fibroma, lipoma, wart, traumatic lesion, mucocele, cyst, abscess, pyogenic granuloma, frictional keratosis, and chemical burn. Employees of RPCI were excluded because they represent a different referent population from the one that the cases came from. The diagnoses of controls were obtained from the RPCI Hospital Information System.

Assessment of Oral Variables

The numbers of teeth with caries, fillings, crowns, and endodontic treatments, as well as the severity of periodontitis and missing teeth, were assessed from panoramic radiographs taken at admission before treatment. Severity of periodontitis was assessed according to extent of ABL in millimeters as described previously.14 One examiner blind to cancer status performed all dental measurements. To establish intraexaminer reliability, duplicate measurements were made on 5 randomly selected patients (110 teeth/207 sites). The κ statistics for the numbers of teeth with caries, fillings, crowns, and endodontic treatments and missing teeth were 0.91, 0.96, 1.00, 1.00, and 1.00, respectively. The mean (SD) differences of duplicate ABL measurements were 0.22 (0.41) mm.

Explanatory Variables

Information on the following variables, obtained at the time of diagnosis, was available in patient records: age at diagnosis, sex, race (white, black, Asian, or other), ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic), marital status (married, single, divorced, widowed, or separated), medical insurance (traditional, Medicare, Medicaid, or uninsured), smoking status (never, former, or current; packs per day), alcohol use (no or yes; drinks per day), tumor stage (I-IV), and tumor differentiation (poor, moderate, well).

Statistical Analysis

Demographic, lifestyle, and clinical characteristics of the study population were summarized by frequency distributions for categorical variables and means with standard deviation for continuous variables. We computed decayed, missing, and filled teeth (DMFT), a widely used measure of caries history.16 To estimate the unadjusted association of HNSCC with dental caries and other exposure variables, crude odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals were calculated from cross-tabulations. Tertiles in the control group were used to categorize exposure variables. The independent association of each exposure variable with HNSCC was estimated from multiple logistic regression analysis. Because of colinearity, each dental variable was evaluated in a separate model. For variable selection, we assessed change in OR when the covariate was added individually to the model. Potential effect modification in the association of dental caries with HNSCC by each covariate was evaluated in stratified analyses and by including multiplicative interaction terms in regression models. A 2-sided P ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS Statistics, version 20.0 (IBM), was used for all data analyses.

Results

A total of 620 participants (399 cases and 221 controls) were included. Of the 399 patients with HNSCC, 146 (36.6%) had a diagnosis of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), 151 (37.8%) of oropharyngeal SCC, and 102 (25.6%) of laryngeal SCC. The prevalences of men (P < .001), smokers (P < .001), alcohol users (P < .001), and married participants (P = .01) were significantly higher among cases compared with controls. The cases were significantly older (mean age, 58.62 vs 54.35 years; P < .001), smoked more cigarettes (mean, 0.69 vs 0.30 packs/d; P < .001), and consumed more alcohol (mean, 0.88 vs 0.31 drinks/d; P < .001) compared with controls. The mean numbers of teeth with caries (1.58 vs 2.04; P = .03), endodontic treatments (0.56 vs 1.01; P = .005), crowns (1.27 vs 2.10; P = .004), and fillings (5.39 vs 6.17; P = .04) were significantly lower among cases compared with controls. Conversely, the severity of ABL (mean, 4.03 vs 2.44 mm; P < .001) and the mean numbers of missing teeth (13.71 vs 8.50; P < .001) were significantly higher among cases compared with controls. The cases were not significantly different from controls with respect to race and ethnicity, access to medical insurance, and DMFT (Table 1).

In univariate analyses, participants in the upper tertiles of caries (OR, 0.37 [95% CI, 0.24-0.58]; P for trend <.001), crowns (OR, 0.46 [95% CI, 0.29-0.75]; P for trend = .01), and endodontic treatments (OR, 0.46 [95% CI, 0.28-0.77]; P for trend = .01) were significantly less likely to have HNSCC compared with those in the lower tertiles. Conversely, participants in the upper tertiles of missing teeth (OR, 2.58 [95% CI, 1.73-3.85]; P for trend <.001) and DMFT (OR, 1.58 [95% CI, 1.02-2.44]; P for trend = .06) were significantly more likely to have HNSCC. After adjustment for age at diagnosis, sex, marital status, smoking status, and alcohol use, participants in the upper tertiles of caries (OR, 0.32 [95% CI, 0.19-0.55]; P for trend = .001), crowns (OR, 0.46 [95% CI, 0.26-0.84]; P for trend = .03), and endodontic treatments (OR, 0.55 [95% CI, 0.30-1.01]; P for trend = .15) were less likely to have HNSCC compared with those in the lower tertiles. Missing teeth and DMFT were no longer associated with HNSCC after adjustment for confounding (Table 2).

Stratified analysis by tumor site has shown that dental caries was associated with HNSCC among patients with oral cavity SCC (OR, 0.30 [95% CI, 0.16-0.57]; P for trend <.001) and oropharyngeal SCC (OR, 0.27 [95% CI, 0.13-0.56]; P for trend <.001) but not among those with laryngeal SCC (OR, 0.89 [95% CI, 0.36-2.23]; Pfor trend = .67) (Table 3).

There were no significant interactions between dental caries and any of the other exposure variables. The association between dental caries and HNSCC remained statistically significant among never smokers (OR, 0.27 [95% CI, 0.09-0.79]; P for trend = .05) and never drinkers (OR, 0.35 [95% CI, 0.19-0.67]; P for trend = .04).

Discussion

We observed an inverse association between dental caries and HNSCC, which persisted among never smokers and never drinkers. This association remained significant among patients with oral cavity and oropharyngeal SCC but not among those with laryngeal SCC. Besides untreated caries, 2 other objective measures of long-standing caries history (endodontic treatments and crowns) were also inversely associated with HNSCC with similar effect sizes. This supports the validity of the association between dental caries and HNSCC, suggesting that it is not likely a chance finding. Missing teeth was associated with increased risk of HNSCC in univariate analyses, but after adjustment for potential confounders, its effect was attenuated and was no longer statistically significant.

An increased risk of HNSCC among subjects with periodontitis was reported previously.13,14 To our knowledge, the present study suggests, for the first time, an independent association between dental caries and HNSCC. An inverse association was an unexpected finding because dental caries has been considered a sign of poor oral health. A limited number of previous studies all used composite indices combining dental caries with other oral variables.17-19 Graham et al17 formed a “dentition index” combining decayed, missing, and septic teeth with oral hygiene and condition of prostheses. After adjustment for smoking and alcohol use, inadequate dentition was associated with an increased risk of oral cavity cancer (Mantel-Haenszel relative risk, 3.15; P < .001). Talamini et al18 defined “general oral condition” as a composite index of decayed teeth, tartar, and mucosal irritation. A poor general oral condition was associated with an increased risk of oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers (OR, 4.5 [95% CI, 1.8-10.9]) after adjustment for age, sex, fruit and vegetable intake, smoking, and alcohol use. In an international study, Guha et al19 defined “general oral health” by the presence of decaying teeth, tartar, gingival bleeding, and mucosal irritation. Poor oral health was associated with an increased risk of HNSCC (oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx) in both central Europe (OR, 2.89 [95% CI, 1.74-4.81]) and Latin America (OR, 1.89 [95% CI, 1.47-2.42]). Because poor oral hygiene, periodontal disease, and missing teeth are all associated with increased risk of HNSCC, an index variable combining these conditions with dental caries will have an apparent positive association with HNSCC, masking the true individual associations.

Mutans streptococci have been suggested as the major cariogenic bacteria, although other acidogenic and aciduric bacterial species including non-mutans streptococci, lactobacilli, actinomycetes, bifidobacteria, and veillonellae also play important roles in the caries process.4 The potential mechanisms by which these commensal bacteria may protect the host from cancer include (1) production of antitumorigenic and antimutagenic compounds; (2) regulation of the cytokine production profile of host cells, promoting cell-mediated response with interferon γ, interleukin 2, interleukin 12, and lymphotoxin α as the prototypic cytokines; (3) production of antimicrobial substances; (4) clearance, inhibition of growth, and downregulation of fimbrial expression of gram-negative bacteria that are potent stimulators of inflammation; (5) production of surfactants; (6) competition with pathogens for adhesion receptors and nutrients; and (7) stabilization of a low pH.20 Interactions between the commensal flora and the host are important for stimulating local mucosal and systemic immunity, tolerance and fine-tuning of T-cell receptor function, epithelial turnover, mucosal vascularity, and lymphoid tissue mass. Dysregulation of such interactions might tip the balance from protective-adaptive to an inflammatory response and result in loss of antitumor effects.20

Supporting our results, a recent study has shown that the prevalence of streptococci in the normal esophagus was significantly higher than that in esophagitis and Barrett esophagus.21 A type 1 microbiome dominated by the genus Streptococcusconcentrated in the normal esophagus, and a type 2 microbiome, characterized by gram-negative anaerobes, was associated with esophagitis and Barrett esophagus. The shift from type 1 to type 2 microbiome was significantly correlated with decreasing levels of streptococci. It has also been shown that patients receiving chemotherapy experience a shift in the oral flora from largely oral streptococci to a more pathogenic gram-negative anaerobic flora that contributes to oral mucositis.22

Whereas caries are localized to tooth surfaces, the commensal cariogenic bacteria are extensively present in saliva and on aerodigestive mucosa. Spread of oral commensals and pathogens to distant body sites by saliva, aspiration, or blood has been demonstrated by many studies.23 Saliva plays an important role in field cancerization by providing a means of transport from 1 surface to another, as well as a means of interaction between different carcinogens.24 In a previous study with the same source population, we had observed that periodontitis, a chronic inflammatory disease, was associated with oral cavity, oropharyngeal, and laryngeal cancers.14 In the present study, dental caries was associated with HNSCC among patients with oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers but not among those with laryngeal cancers. Almost all patients with laryngeal cancer (98%) had a history of smoking, compared with 76% and 78% of patients with oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. They also consumed significantly greater amounts of tobacco and alcohol, were older, and had more missing teeth.

The number of missing teeth was associated with increased HNSCC risk in univariate analysis, but its effect size was attenuated and lost statistical significance after adjustment for explanatory variables. Whereas few previous studies reported a positive association between tooth loss and HNSCC,25-27 most studies, similar to ours, reported a nonsignificant association after adjustment for confounding.18,19,28,29 Missing teeth can be misleading as a surrogate measure for caries or periodontitis when their relationships with HNSCC are assessed because the etiologies, as well as the outcomes, of these 2 diseases are very different. Because periodontitis is associated with an increased risk of HNSCC, the risk will increase proportional to the number of affected teeth. Conversely, if dental caries is inversely associated with HNSCC, the risk will decrease proportional to the number of affected teeth. Therefore, the association between missing teeth and HNSCC depends on the reason for tooth loss. The number of DMFT was also not associated with HNSCC in the present study, which was not a surprise. The number of DMFT is a measure of dental caries with a long record of use in the literature and is widely accepted around the world.16 However, it is a composite index combining untreated dental caries with missing teeth and fillings, and for the reasons discussed here, it does not represent dental caries history accurately.

Missing teeth is a difficult issue to deal with especially in retrospective studies when the reason for tooth loss is unknown. In our initial analyses, we assessed the effect of missing teeth as a potential confounder and an effect modifier. Dental caries was not significantly correlated with missing teeth (r = −0.012). When missing teeth was added as a covariate to the model, the change in the main effect estimate (OR) was only 0.02, suggesting that missing teeth was not a significant confounder. In addition, potential effect modification by missing teeth was evaluated in stratified analyses and by including an interaction term in the multiple logistic regression. There was no significant interaction between missing teeth and caries (P = .77). The association between dental caries and HNSCC remained significant in subjects with low, moderate, and high numbers of missing teeth (categorized by tertiles) with similar effect sizes in all strata.

The present study analyzed existing data, and the information on certain potential confounders, including socioeconomic status (SES), diet, and HPV status was not available. The SES variables are highly correlated with each other, with higher education usually leading to higher income, better residence, and better health insurance.30,31 Therefore, surrogate variables of SES, such as zip code or medical or dental insurance, may be used when data on traditional SES variables such as education and income are not available. In the present study, the only standard SES variable available for all study participants was medical insurance, and 51.5% had employer-sponsored insurance, 33.7% had Medicare, 10.3% had Medicaid, and 4.5% were uninsured. According to the Census Bureau’s 2011 Current Population Survey, 55.3% of the US general population is covered by employer-sponsored insurance, 14.5% by Medicare, 15.9% by Medicaid, and 16.3% is uninsured.31 Although the proportions of employer-sponsored insurance and Medicaid in our study population were similar to those of the general US population, the proportion of subjects with Medicare was higher and the proportion of uninsured subjects was lower. This is expected because our study population is hospital-based and older.

Frequent consumption of sugar is an important factor in the etiology of dental caries.4 On the other hand, an inverse association between fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of HNSCC is well established.17,20 It is likely that sugar and acid in fruits contributed to the higher frequency of dental caries in controls while lowering their risk of HNSCC. Therefore, the role of diet in the association between dental caries and HNSCC needs to be assessed in future studies.

Data regarding HPV status were available for a subset of patients with cancer. Among 125 patients with known HPV status, the mean numbers of teeth with dental caries (1.37 vs 1.86; P = .37), fillings (5.25 vs 5.40; P = .86), endodontic treatments (0.46 vs 0.57; P = .63), and crowns (0.90 vs 0.93; P = .95) were not significantly different in patients with HPV-negative and HPV-positive tumors, suggesting that HPV is not likely to influence the effect estimate. In addition, there is no known association between dental caries and oral HPV infection.

Another limitation of the study is that detailed data on dental caries, including their depth and location, were not available. It is known that radiographs underestimate the frequency and extent of dental caries, especially in early stages.32However, because the same methods were used for cases and controls and all measurements were performed by 1 examiner blind to cancer status, the measurement bias is not likely to be significant and would only lead to underestimation of the true effect.33 The radiographs from which dental caries was assessed were obtained at the time of diagnosis before cancer treatment was initiated. Dental caries is a chronic disease, which starts and progresses slowly, and detectable dental caries on radiographs reflects preexisting disease history. Therefore, despite the case-control design of the present study, existing data provide evidence of temporality that dental caries preceded cancer diagnosis.

An important strength of the present study is that the cases and controls were selected from the same source population, the same way. All case and control patients with new diagnoses who met the inclusion criteria during the study period were included without knowledge of their dental status. Therefore, the selection bias in this study is also not likely to be significant.33

Although the importance of the local environment for carcinogenesis is widely accepted, research evaluating the role of oral factors in the natural history of HNSCC is lacking. If confirmed by other studies, the findings of this study have important implications for the management of HNSCC, as well as oral infections. It is important to remember that the majority of commensal bacteria are beneficial to the host, and streptococci are the most abundant genus in the oral cavity (52%).34Cariogenic bacteria are part of the commensal oral flora, and their presence is not sufficient to cause dental caries in the absence of the other risk factors, such as dental plaque, frequent consumption of a carbohydrate-rich diet, and reduced saliva production.4 Caries is a dental plaque–related disease. Lactic acid bacteria cause demineralization (caries) only when they are in dental plaque in immediate contact with the tooth surface. The presence of these otherwise beneficial bacteria in saliva or on mucosal surfaces may protect the host against chronic inflammatory diseases and HNSCC. We could think of dental caries as a form of collateral damageand develop strategies to reduce its risk while preserving the beneficial effects of the lactic acid bacteria. For example, antimicrobial treatment, vaccination, or gene therapy against cariogenic bacteria may lead to more harm than benefit in the long run, including a shift in microbial ecology toward gram-negative bacteria and increased risks of chronic inflammatory diseases and cancer. Instead, strategies preserving microbial ecology beneficial to the host such as mechanical plaque control, preservation of saliva, and use of fluoride, as well as control of diet and other risk factors, might be wiser. Future studies assessing the potential effects of the oral microbiome and associated immune responses on HNSCC will help elucidate the biological mechanism of the clinical association that we have observed in this study.

Article Information

Corresponding Author: Mine Tezal, DDS, PhD, State University of New York at Buffalo, 202 Foster Hall, Buffalo, NY 14214 (mtezal@buffalo.edu).

Submitted for Publication: April 3, 2013; final revision received June 18, 2013; accepted July 22, 2013.

Published Online: September 12, 2013. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2013.4569.

Appendix D:

These are two newsletters published by the AAE. Current research directly contradicts some of the statements and assumptions presented in these newsletters.

Compare what the AAE states in these newsletters to the actual peer reviewed scientific article presented and see what is true, what is misleading, and what is completely false in these AAE newsletters.

Selected References for Spring/Summer 2000

ENDODONTICS: Colleagues for Excellence

Oral disease and systemic health: What is the connection?

American Association of Endodontists. Root canal therapy safe and effective, Endodontics: Colleagues for Excellence. F/W 1994.

American Heart Association recommendations. Prevention of bacterial endocarditis, JAMA 1997;227:1794-1801.

Baumgartner, J C et al. The incidence of bacteremias related to endodontic procedures I. Nonsurgical endodontics J Endodon, 1976;2:135-140.

American Association of Endodontists, The incidence of bacteremia in endodontic manipulation – preliminary report Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol, 1960;

Peters, LB et al, The fate and the role of bacteria left in root dentinal tubules, Int Endod J, 1995;28:95-99.

American Academy of Periodontology Periodontal disease as a potential risk factor for systemic diseases J Periodontology 1998;69:841-850.

Beck J et al, Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease, J Periodontology 1996;67:1123-1137.

Offenbacher, S et al, Periodontal infection as a possible risk factor for preterm low birth weight, J Periodontology 1996;67:1103-1113.

Slots, J Casual or causal relationship between periodontal infection and non-oral disease? J Dent Res 1998;77:10.

Herzber MC and Meyer MW Effects of oral flora on platelets: Possible consequences in cardiovascular disease, J Periodontology 1996;67:1138-1142.

Grossman LI, Root Canal Therapy. 4th Edition. Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia. pp. 18-24, 1940.

Appendix E:

Biographical profile of Jerry Bouquot, DDS, MSD.

Dr. Jerry Bouquot earned his DDS and MSD degrees from the University of Minnesota, with postdoctoral fellowships to the Mayo Clinic and the Royal Dental College in Copenhagen, Denmark as the recipient of a Career Development Award from the American Cancer Society.

He holds the record as the youngest oral pathology chair in U.S. history and for more than 26 years was chair of two diagnostic science departments, one in West Virginia University and the other at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

He has received more than 50 honors and awards, including WVU’s highest awards for teaching and service to humanity, and its alumni association’s Lifetime Achievement Award. He received the St. George National Award, the highest award given by the American Cancer Society for lifetime efforts in cancer control, and has been awarded the Bridgeman Distinguished Dentist Award from the West Virginia Dental Association, the Distinguished Leadership Award from the West Virginia Public Health Association, a Presidential Certificate of Appreciation from the American Academy of Oral Medicine, Honorary Life Membership from the International Association of Oral Pathologists, the Distinguished Alumnus Award from the University of Minnesota and both the Fleming and Davenport Award for Original Research and the Award for Pioneer Work in Teaching & Research from The University of Texas.

He is now a retired adjunct professor of The University of Texas and West Virginia University, and remains the director of research for his private research center, the Maxillofacial Center for Education and Research.

He has been director of two of the largest U.S. oral pathology biopsy services, one of which received tissue from 45 states and five foreign countries. He has been the dental director of the West Virginia Bureau for Public Health, a Senior Visiting Scientist of the Mayo Clinic, a Special Advisor to the National Institutes of Health, an Honorary Member of Dental Informatics of the University of Göteborg, Sweden, a Gorlin Visiting Professor of the University of Minnesota, and the Oral Cancer Control Coordinator for the state of West Virginia.

He has been a consultant to Pittsburgh Children's Hospital and the New York Eye & Ear Infirmary. He has been awarded Fellowship in the International College of Dentists, the American College of Dentists, the Academy of Dentistry International, the American Academy of Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology and the Royal Society of Medicine (U.K.); he has been on the Scientific Advisory Boards of four U.S. and European corporations. During his career, he peer-reviewed more than 1,500 scientific papers for more than 40 journals.

Dr. Bouquot has more than 340 published papers, abstracts, books and book chapters. His work has been translated into numerous languages, has been cited more than 6,000 times in the literature, and has been used by state and national governments to determine oral health policy.

He is co-author of the most popular textbook of oral pathology, has named more than three dozen oral diseases, has been a reviewer for more than 40 medical and dental journals, and has been on the editorial boards of four international dental journals. He has presented more than 1,600 research and continuing education seminars in more than 30 countries and all 50 U.S. states, and has taught what are possibly the longest-running community-based CE courses in U.S. dentistry. His informational websites are the two most popular oral pathology sites on the internet, together getting almost 6.5 million hits annually.

Dr. Bouquot is a past president of the American Board of Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology, the Eastern Society of Teachers of Oral Pathology, the Western Society of Teachers of Oral Pathology, the Organization of Teachers of Oral Diagnosis, four regional dental societies, and the West Virginia Division of the American Cancer Society. He has been a member of the Executive Council of the American Academy of Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology, the national Board of Directors of the ACS and the Board of Trustees for the eight-state South Atlantic Division of the ACS. As a member of the ACS National Research Committee, he was among those responsible for reviewing and approving more than $90 million in cancer research grants annually.

Board Certification

American Board of Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

APPENDIX F:

APPENDIX G: Weston Price Bio

APPENDIX H: Easlick and Grossman references used by the AAE. I believe that it is important to see the actual articles used to refute focal infection and see how they hold up to current peer reviewed research.

Some of the assumptions used by Easlick and Grossman to debunk focal infection have since been proven false and therefore do not debunk focal infection.

Interestingly, the AAE cites these two studies and authors as their number one and number two references on the safety of root canal teeth.

APPENDIX I:

Dr. Oz Is No Wizard, but No Quack, Either

By Bill Gifford

April 25, 2015

ONE afternoon last December, my book publicist called with the best possible news: “You’re booked on ‘The Dr. Oz Show’!” she crowed. This was a huge coup, and I tried to sound as thrilled as she was.

Secretly, my heart sank. Dr. Oz? As a serious science writer and devout skeptic, I knew I was supposed to scorn him.

He’d been savaged on social media for months. Last June, Senator Claire McCaskill, Democrat of Missouri, had given him a public tongue-lashing for touting a supplement called green coffee bean extract, which he had called “a magic weight loss cure for every body type,” among other over-the-top statements. His enthusiasm was based on a single small study that later turned out to be bogus, and was eventually retracted. Oops. His critics had a field day.

Then, in December, The BMJ, a British medical journal, published a study claiming that fewer than half of the on-air recommendations on “The Dr. Oz Show” were supported by scientific evidence. I happened to be taping my segment that day, and my new pal, Dr. Oz, seemed rather tense. When I said something positive about the health benefits of red wine, he remarked sardonically, “That’s good, because I talk about it all the time.”

Earlier this month, a group of 10 self-described “distinguished physicians” piled on with a letter urging Columbia University to fire Dr. Mehmet Oz from his post as vice chairman of the department of surgery. “Dr. Oz has repeatedly shown disdain for science and for evidence-based medicine,” they wrote. “Worst of all,” they went on, “he has manifested an egregious lack of integrity by promoting quack treatments and cures in the interest of personal financial gain.”

On Thursday, an indignant Dr. Oz fired back, saying that he does not endorse or profit from the products he promotes. He also went after his critics personally. Several have ties to an industry-funded advocacy group, he noted, and one — Dr. Gilbert Ross — did prison time for Medicaid fraud, which is an odd definition of “distinguished.”

The ad hominem exchange was unfortunate. A more careful look, however, at the merits of the supposed case against him makes it start to look weaker than a cup of green coffee.

That BMJ study, for example: When researchers analyzed 80 “randomly selected” recommendations from “The Dr. Oz Show,” they judged that 26 of them, or 33 percent, were supported by evidence they deemed “believable.” They found just nine recommendations that were contradicted by convincing scientific literature. Looked at this way, Dr. Oz is proved wrong only 11 percent of the time — not ideal but hardly “egregious.” The BMJ authors also didn’t list the statements they examined and the evidence for or against, so it’s hard to know how serious these errors might have been.

The show on which I appeared aired on Feb. 19, and it featured the author of “The Bra Book,” and the story of a woman who didn’t know she was pregnant until shortly before she gave birth. The comedian Wanda Sykes talked about hot flashes, some women did yoga-type exercises, and there was a segment on “back boobs,” whatever those are.

It was a surreal experience, but this is what Dr. Oz does. He covers health-related subjects — like bowel movements, menopause and body fat — that many people find awkward to discuss, even taboo. Much of what Dr. Oz talks about is pretty anodyne stuff: Eat fruit! Exercise! Sleep right! Diet features prominently on every show: The celebrity chef Rocco DiSpirito demonstrated supposed fat-burning recipes on the show in which my segment appeared.

It’s hard to complain about a guy advising American families on how to cook healthier meals. Do we really need double-blind clinical trials of Mr. DiSpirito’s recipes? Must “The Bra Book” be submitted for peer review? This is daytime television, not the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Yet these are not things that you’ll hear much about in a typical 15-minute visit to your doctor. Despite mounting evidence that diet is crucial to health, most medical schools offer only rudimentary training in nutrition. A 2011 study found that only 45 percent of overweight patients had been alerted to the fact by their doctors. For obese patients, the figure was even worse: Nearly two-thirds hadn’t gotten this message. Given the overwhelming evidence on the health hazards of obesity, shouldn’t it be more like 100 percent?

The doctors’ letter raises an interesting question: Is “evidence-based medicine” itself always a settled issue? In scientific inquiry, the “truth” is slipperier and more fluid than distinguished physicians will generally admit. Different doctors take different approaches to issues like whether or not to prescribe statin drugs to patients with high cholesterol, or how to treat people with pre-diabetes.

Some are quick to prescribe medications, whereas Dr. Oz tends to favor less interventionist, more natural approaches based on diet and exercise. Again, hard to see the problem there — especially in the context of a television show when direct-to-consumer advertising of pharmaceuticals pervades the airwaves. (The only other country that permits marketing like this is New Zealand.)

One of the products frequently advertised on TV, for example, is testosterone replacement therapy, for a condition called “low T.” In March, the Food and Drug Administration issued a stern warning to physicians and makers of “low T” treatments, saying the medications have been overprescribed for age-related applications and could lead to an increased risk of stroke and cardiovascular problems. Dr. Oz, meanwhile, has devoted more than one segment to exploring natural ways to deal with “low T” symptoms like low energy, poor sex drive, weight gain and depression.

A diversity of medical opinion is not a bad thing; in fact, far from it. Today’s fringe treatments could well become tomorrow’s standard protocol.

For example, the American Heart Association’s cholesterol guidelines focus on the “good” and “bad” types of cholesterol (H.D.L. and L.D.L., respectively). But this largely ignores another biological marker, a lipoprotein known as ApoB, which a growing body of research has shown to be a much better predictor of heart disease risk. The evidence points in a new direction, yet the A.H.A. guidelines lag behind.

Progress in medicine and science is a messy, contested affair. It can be hard to know who’s right or wrong until the dust has settled and time has passed. Without people pushing the boundaries of accepted treatments and conventional wisdom — and fostering dialogue, which Dr. Oz sees as part of his mission — there would be no advancement.

Here in America, rightly or wrongly, we have clearly chosen a wild and woolly marketplace where free speech comes before regulation and expert ruling. That means that, as patients and consumers, we need to do our own homework and exercise another precious right: the right to a second opinion. And then, maybe, a third.

APPENDIX J

Remembering Roger Boisjoly: He Tried To Stop Shuttle Challenger Launch

By Howard Berkes 2012

Roger Boisjoly was a booster rocket engineer at NASA contractor Morton Thiokol in Utah in January, 1986, when he and four colleagues became embroiled in the fatal decision to launch the Space Shuttle Challenger.

Boisjoly was also one of two confidential sources quoted by NPR three weeks later in the first detailed report about the Challenger launch decision, and the stiff resistance by Boisjoly and other Thiokol engineers.

The experience both haunted and inspired Boisjoly in the decades that followed. We learned this weekend from this story in The New York Times that Boisjoly died last month in Utah at age 73.

Bulky, bald and tall, Boisjoly was an imposing figure, especially when armed with data. He found disturbing the data he reviewed about the booster rockets that would lift Challenger into space. Six months before the Challenger explosion, he predicted "a catastrophe of the highest order" involving "loss of human life" in a memo to managers at Thiokol.

The problem, Boisjoly wrote, was the elastic seals at the joints of the multi-stage booster rockets. They tended to stiffen and unseal in cold weather and NASA's ambitious shuttle launch schedule included winter lift-offs with risky temperatures, even in Florida.

On January 27, 1986, the forecast for the next morning at the Kennedy Space Center included a launch-time temperature as low as 30 degrees Fahrenheit. NASA had never launched in temperatures that cold and Boisjoly and his four colleagues at Thiokol headquarters in Utah concluded it would be too dangerous too launch.

Three weeks later, he told NPR's Daniel Zwerdling in an unrecorded and confidential interview, "I fought like Hell to stop that launch. I'm so torn up inside I can hardly talk about it, even now."

But Boisjoly did talk about it in a hotel room in Alabama, revealing for the first time the details of that effort to keep Challenger on the launch pad. He asked that he not be named but he agreed to be quoted anonymously. As he spoke with Zwerdling, a second engineer revealed the same details to me under the same conditions at his home in Brigham City, Utah.

Boisjoly's family agreed to release him from our pledge of confidentiality so that his efforts to get the truth out can be widely known.

"We all knew what the implication was without actually coming out and saying it," a tearful Boisjoly told Zwerdling in 1986. "We all knew if the seals failed the shuttle would blow up."

Armed with the data that described that possibility, Boisjoly and his colleagues argued persistently and vigorously for hours. At first, Thiokol managers agreed with them and formally recommended a launch delay. But NASA officials on a conference call challenged that recommendation.

"I am appalled," said NASA's George Hardy, according to Boisjoly and our other source in the room. "I am appalled by your recommendation."

Another shuttle program manager, Lawrence Mulloy, didn't hide his disdain. "My God, Thiokol," he said. "When do you want me to launch — next April?"

These words and this debate were not known publicly until our interviews with Boisjoly and his colleague. They told us that the NASA pressure caused Thiokol managers to "put their management hats on," as one source told us. They overruled Boisjoly and the other engineers and told NASA to go ahead and launch.

"We thought that if the seals failed the shuttle would never get off the launch pad," Boisjoly told Zwerdling. So, when Challenger lifted off without incident, he and the others watching television screens at Thiokol's Utah plant were relieved.

"And when we were one minute into the launch a friend turned to me and said, 'Oh God. We made it. We made it!'" Boisjoly continued. "Then, a few seconds later, the shuttle blew up. And we all knew exactly what happened."

Until NPR's story, the special commission investigating the Challenger tragedy hadn't even interviewed all the engineers involved in the pre-launch debate.

The explosion of Challenger and the deaths of its crew, including Teacher-in Space Christa McAuliffe, traumatized the nation and left Boisjoly disabled by severe headaches, steeped in depression and unable to sleep. When I visited him at his Utah home in April of 1987, he was thin, tearful and tense. He huddled in the corner of a couch, his arms tightly folded on his chest. But he was ready to speak publicly.

"I'm very angry that nobody listened," Boisjoly told me. And he asked himself, he said, if he could have done anything different. But then a flash of certainty returned.

"We were talking to the right people," he said. "We were talking to the people who had the power to stop that launch."

Boisjoly testified before the Challenger Commission and filed unsuccessful lawsuits against Thiokol and NASA. He continued to suffer and was ostracized by some of his colleagues. One said he'd drop his kids on Boisjoly's doorstep if they all lost their jobs, according to his wife Roberta.

"He took it very hard," she recalls. "He had always been held in such high esteem and it hurt so bad when they wouldn't listen to him."

A therapist recommended speaking out even more and for close to three decades, Boisjoly traveled to engineering schools around the world, speaking about ethical decision-making and sticking with data. "This is what I was meant to do," he told Roberta, "to have impact on young people's lives."

Boisjoly continued to respond to emails and letters from engineering students right up until his sudden death in his sleep last month in St. George, Utah. He was diagnosed with cancer two weeks before.

"He always stood by his work," Roberta recalls, her voice breaking. "He lived an honorable and ethical life. And he was at peace when he died."

Challenger's Whistle-Blower: Hero And Outcast

The engineer who opposed the doomed launching of the shuttle finds himself ostracized as he embarks on several new careers. PHOENIX--When the shuttle Challenger blew up, the explosion lit a fuse in Roger Boisjoly's conscience. A structural engineer for Morton Thiokol Inc., the firm that later bore blame for the disaster, Boisjoly had argued against the launch the night before and, like the rest of the nation, watched in horror when the shuttle blew up. "I left the room and went directly to my

Jan 20, 1990

ELIZABETH PENNISI

5

The engineer who opposed the doomed launching of the shuttle finds himself ostracized as he embarks on several new careers.

|

PHOENIX--When the shuttle Challenger blew up, the explosion lit a fuse in Roger Boisjoly's conscience. A structural engineer for Morton Thiokol Inc., the firm that later bore blame for the disaster, Boisjoly had argued against the launch the night before and, like the rest of the nation, watched in horror when the shuttle blew up. "I left the room and went directly to my office where I remained in shock the rest of the day," he recalls about that terrible morning four years ago this week.

During the next eight months, Boisjoly would become both a national hero and a professional pariah. Although widely lauded for his courage in alerting the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and his company to the dangers in the design of the space vehicle's booster rockets and for his frank testimony to a presidential commission investigating the accident, he has paid a terrible personal price for his actions. He was ostracized by most of the 1,600 residents of Willard, Utah, where Morton Thiokol is based and where, just three years earlier, he had served as mayor. And his life at Morton Thiokol, which made the faulty booster rockets, became unbearable.

"He acted to protect the public interest at a significant cost to his health and professional well-being," says Mark Frankel, head of the scientific freedom and responsibility program at the American Association for the Advancement of Science, which gave Boisjoly its annual award in 1988. "He made every effort to act responsibly, and for that he has paid a high price."

Now Boisjoly and his wife live in Mesa, Ariz., a suburb of Phoenix. He has set up his own consulting business and hopes to work primarily for lawyers, as a technical expert. His business card states his philosophy, as well as his place in history: "Vigorously Opposed Launching Space Shuttle Challenger."

Over these past four years Boisjoly has wrestled daily with an issue that all scientists fear but few have to face: When does one speak out? And at what price to one's career? And to one's company? As an engineer, Boisjoly might put it in more technical terms: How does one determine the appropriate risk of one's actions?

As a consultant for General Motors, Ron Westrum is trying to stimulate creativity within a corporate structure. Last year, he decided that Roger Boisjoly should be one of his program's key speakers. "I'm sure that in many corporations, somebody like Roger would have been looked down upon," says Westrum, a professor of sociology and interdisciplinary technology at Eastern Michigan University in Ypsilanti. "But we're trying to change that." Westrum respects Boisjoly's honesty, openness, and courage, and he hopes that the lessons from the Challenger accident will encourage employees to speak out when they see a problem and help managers to be more receptive to those comments. "If companies tend to dismiss information about danger, then they are also likely to dismiss information about innovation," says Westrum. Boisjoly's lectures generally trace the details leading up to the final meeting before the scheduled launch of the Challenger. In the meeting Morton Thiokol executives capitulated to pressure from NASA and gave their assent to the launch despite concerns from engineers about the effect of the freezing temperatures on the seals of the booster rocket. It is not enough for engineers to be able to assess risk, Boisjoly tells his audiences. If there is danger of injury or loss of life, an engineer must be able to communicate that risk and work to prevent damage. He recounts how he tried to raise the red flag, first by working within his company through memos to his superiors and, later, through direct warnings to NASA, the customer. The memos went unheeded, and his objections were overruled. His standards for assessing risk are high, perhaps higher than corporate planners can justify. But he sees no alternative, and the Challenger accident bears out his worse fears. Despite his concerns, he reminds himself, the launch proceeded. He has turned that experience into a campaign for stronger professional ethics and for the need to speak out against risk. He visits college campuses about twice a month, where his message is well-received. "The students see him as a role model," says William Middleton, chairman of the ethics committee for IEEE USA. "I think he will do a great deal to change the ethical perspective [of future engineers]." Westrum and others think Boisjoly has a broader message as well. "It's very important for high-technology firms to do what they can to speed the flow of technological information," he says. "Roger has a lot to say about why information did not flow." MIT officials have also invited him to talk to students - not about Challenger, but about what it's like to be an engineer in a big corporation. In the coming months he will visit a second General Motors plant and at least one other corporation. It's essential that information flow smoothly and that corporations listen more closely to people like Boisjoly, Westrum asserts. "If they don't," he warns, "this country will continue to go down the tubes." --E.P. |

Not surprisingly, his former employer does not share Boisjoly's eagerness to discuss his actions and their meaning. A spokesman for Morton Thiokol declined to comment on any matter relating to Boisjoly, saying that the subject is closed. But colleagues applaud Boisjoly's efforts to raise the issue of professional ethics and to stress its importance.

"He's one of a very small group of people who have had the courage of their convictions," says William Middleton, chairman of the ethics committee for the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). "He took the matter into his own hands and dealt with it by going public on a whistle-blowing campaign. And now he's sort of blacklisted. To those of us who do work in the ethics area, he's a hero."

Boisjoly, now 51, had no idea he would ever play such a role when he went to work for Morton Thiokol in 1980 as a structural engineer. His job then was to analyze the cases that enclosed the space shuttle's solid rocket boosters. He used data from past flights to generate flight-readiness updates for NASA, and eventually became a technical trouble- shooter for the company.

In late 1985, he became one of five engineers in charge of redesigning the seals and joints on the booster rockets. He became increasingly concerned about the ability of the seals to work properly at extreme temperatures. Although he passed his worries along to his managers, the problems were never given a high priority.

On the night before the January 1986 launch, Florida experienced a statewide cold snap. The weather prompted a teleconference between NASA and Morton Thiokol that ended, despite the engineers' objections, in a decision to go ahead with the launch. Boisjoly's subsequent testimony to a presidential commission and later to Congress helped government investigators learn about the process that contributed to the tragedy. He and two other engineers helped interpret the technical data for the committees and were more willing than Morton Thiokol to provide details of the events leading up to the launch.

Following the disaster, Boisjoly stayed on at Morton Thiokol as a senior engineer involved in redesigning the faulty seals. But he says he was not allowed to interact with NASA, nor was he given much responsibility by his superiors. "Instead," he recalls, "they put me through hell on a day-to-day basis." He became sick and depressed, a condition that doctors diagnosed as posttraumatic stress disorder. In June 1986, after testifying before Congress, he stopped going to work and went on extended sick leave. In January 1987 he began receiving long-term disability pay, collecting 60% of his salary until the benefits ran out in January 1989.

Now he's hopeful that his integrity, knowledge, and experience will attract clients to his fledgling consulting practice. "Attorneys that care and do stand for facts will want me," Boisjoly asserts.

Few engineers can match Boisjoly's track record of testifying under pressure. He was also grilled by FBI agents and officials from the Justice Department about his work analyzing technical data. "They were asking hard questions about what really happened," he recalls.

"It's engineering work plus what a lot of people cannot do - get up and communicate your findings in an adversarial environment."

Boisjoly has registered with two services that provide expert witnesses to attorneys, and he's paid to have his name added to a national directory. Last summer he sent handwritten notes to a dozen editors and reporters who had interviewed him, asking them for referrals. As a consultant he plans to provide lay interpretations of technical specifications and can determine whether a product meets the required standards. "It's just a matter of getting a match and showing people what I can do," he says.

But, so far, Roger Boisjoly's unique brand of engineering expertise is not much in demand. It takes time, he says, for lawyers to get to know what he has to offer. He did one day's worth of work examining a product that failed on a helicopter, and he's fielded a few calls from prospective clients. He fills the hours by revising his talk, making telephone calls, and puttering about the house. He's also written a few magazine articles and a technical paper for the American Society of Civil Engineers.

"The hardest part is getting over the frustration of knowing that we are barely eking out an existence while waiting for something to happen," he says. "I think there is a limit to how much a human being can take." In the meantime, his wife stays busy helping her daughter with a new baby, and the two of them are getting to know their neighbors.

Boisjoly is most visible on the college lecture circuit. He's given more than 70 talks in the United States, Canada, and Norway about his role in the accident and the investigation, and he still visits campuses about twice a month.

Until recently, his fees from speaking engagements barely covered his expenses, and the talks were chiefly therapeutic. Now they are a financial necessity, he says. "It's these talks and the honoraria that keep us floating."

His peers also appreciate his message. In 1988 he spoke to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers to pick up that group's Founders Award. A year earlier the National Space Society cited him with its presidential award. He has also been honored by IEEE USA.

The reaction to Boisjoly's 1988 speech before IEEE's professional activities section in Phoenix was typical of how most professional organizations view him. "It very deeply moved a whole bunch of our members," recalls Ed Bertnolli, IEEE vice president for professional activities. "He appeared to have been ethical in his attempt to protect the public, and he kind of got his head chopped off."

But Boisjoly has learned that praise is not the same thing as professional advancement. "Roger is a very talented technical person," says IEEE's Middleton, a retired engineer who worked for Bell of Pennsylvania. "He has a fine method of articulating his viewpoint. But he's such a public figure, any personnel director would have real concerns from a corporate standpoint of hiring somebody with such a high visibility. When they [whistle-blowers] go public, it obviously makes the career path a difficult one to follow."

Boisjoly says he has no regrets about the new direction his life has taken. But he says that the past few years have not been easy ones. "People have the wrong concept of what a whistle-blower is," he says. He insists that he's not a crusading radical, but he makes clear that he's not the type to run away from a problem he uncovers.

Boisjoly feels that a variety of duties during a 27-year career as an engineer should have paved the way for a good position near his new hometown of Mesa. But that hasn't been the case. In November 1988, he sent out 150 resumes to aerospace companies in Arizona. He got back one nibble. "It might have been because the industry has been down," he says, "or it might have been who I am and what I did.

"Industry is very reticent of hiring someone who has a mind of his own," he says. "After eight months [of waiting], I figured, `Why kid myself?' " He had spent the summer boning up in Florida for the professional engineering exams, which he took in October. Last March he was certified to set up his own company.

What hurts more than the lack of a good job is the realization that he and his wife couldn't stay in Willard. They had moved to that one-company town in 1980. They bought a house on about two acres of land with the idea that they'd settle down once he retired from Morton Thiokol. "But it was not going to be allowed to happen," he says. "Everyone was against us." Understandably, his neighbors were worried that his crusade would jeopardize their own livelihoods.

So far, those fears are unfounded. The economic outlook for Willard appears bright. Morton Thiokol has six shuttle flights left on its $2.9 billion NASA contract for the solid rocket motors, and it's competing for the chance to build rocket motors for the next 66 shuttle flights.

As far as Morton Thiokol is concerned, the Challenger is a closed chapter in U.S. space history. The company has no official comment about either the accident or Boisjoly. Two other engineers who were prominent for a brief time after telling investigators that they had opposed their company's decision to launch have elected to stay at Morton Thiokol. One, Al McDonald, is now a vice president, and the other, Arnie Thompson, is a manager. They follow their company's lead in refusing to speculate about the impact of the Challenger accident on the company and their lives.

NASA, too, seems more concerned with looking ahead than looking back. It sent 30 people to Morton Thiokol to bolster the effort to redesign the booster rockets and to calm fears about the future.

"It was a very intense, emotional undertaking, with a lot of energy spent trying to put the bad feelings behind us," says Royce Mitchell, NASA manager for the solid rocket program. "So many people did not know what would happen in terms of their jobs, their self-respect, and their image."

Although Mitchell admits that the constant oversight during the redesign project was burdensome, he believes that the effort contributed to better rapport between all members of the team. "It got a lot of people in the habit of being open and communicating and floating problems up the line," he says. "People openly and freely discuss things that in the past I am sure were not discussed. There are multiple lines of communications that we all want to maintain."

It may still be too early to know how history will ultimately remember Roger Boisjoly. But this winter, the American Broadcasting Co. will take a stab with a made-for-television movie that chronicles the six months leading up to the shuttle disaster. Boisjoly will be played by actor Peter Boyle.

George Englund, Jr., one of the producers of "The Challenger," says that in the movie, "Boisjoly is perceived by Morton Thiokol as a kind of pain in the ass. He's both a pariah and a hero. He was perceived by some people as a hero, but he's also perceived as a Chicken Little who was constantly saying `the sky is falling.' " Boisjoly was interviewed extensively as the production was under way, and was given the script to review.

Regardless of how Boisjoly is ultimately labeled, those like IEEE's William Middleton and General Motors Corp. consultant Ron Westrum (see accompanying story), who follow professional ethics issues, say that society needs these so-called Chicken Littles. "I would encourage people to be courageous, even if the penalty is stiff," says Westrum.

He hopes Boisjoly will be an inspiration to reticent employees, such as the 300 GM engineers and managers who heard Boisjoly describe his agony as he watched the Challenger explode. "It's a very potent warning about what they may have to face if they don't stand up for what they believe in," says Westrum.

APPENDIX K:

Yes, Licensing Boards Are Cartels

The case for why Congress should get involved.

Eric Boehm|Sep. 13, 2017 9:05 am

Licensing boards are perhaps the most powerful labor institution in American history.

The best estimates available suggest that roughly 30 percent of American workers are now required to get a license from one of those quasi-government agencies before they can enter the workforce. That's about the same percentage of the workforce that was a member of a union in the 1950s, the decade when union membership peaked before falling off to about half that percentage today.

There's no debate about whether the federal government has a role to play in regulating the activities of labor unions, of course. Should Congress do something about licensing boards?

"I think federal interest in this is really important," says Rebecca Allensworth, a professor of law at Vanderbilt University.

The "dirty secret behind licensing boards," Allensworth told the House Judiciary Committee on Tuesday afternoon, is that very little of what they do resembles government activity. While growing to become the largest labor institution in American history, they have too often become a self-serving institutions that act like cartels instead of protectors of public health and safety.

In research she published last year, Allensworth looked at all 1,790 state occupational licensing boards operating in America. Of those, she found that 1,515 (85 percent) of them were required by state statute to be comprised of a majority of currently licensed professionals in the same field.

"These boards are formed, by law, as cartels," Allensworth said Tuesday.

State legislatures have increasingly outsourced professional regulation to licensing boards, and in theory that's not necessarily a bad idea. Professionals working in a given field are likely to have more expertise about what rules might be needed. But in exchange for expertise, states have created the potential for professional self-dealing.

And that's not just theoretical. It's very real. In North Carolina, for example, a board comprised by a majority of actively practicing dentists decided in 2012 to send cease-and-desist letters to kiosks offering teeth whitening services. The practice of whitening teeth, the board declared, could only be done by licensed dentists.

In that instance, the Federal Trade Commission intervened. The whole case wound up in the Supreme Court, which ruled in 2015 that licensing boards controlled by a majority of "active market participants" could not make deliberately anticompetitive rules, unless those boards were "actively supervised" by some other element of state government.

Some states have responded to the Supreme Court ruling by changing how their boards operate, but the North Carolina Board of Dental Examiners v. FTC case created more questions than answers.

That's why Congress is now getting involved. In July, Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Calif.), along with three Republican senators, introduced the Restoring Board Immunity Act to clarify how state licensing boards need to be structured in order to avoid potentially expensive lawsuits challenging boards' anticompetitive rules.

In the end, licensing issues will be settled at the state level. Issa's bill is merely intended to steer states towards potential solutions to the problems created by the 2015 Supreme Court ruling. Among other things, states would have to pass legislation requiring lawmakers to conduct comprehensive reviews of their licensing boards every five years. Those would include a cost/benefit analysis and an assessment of any new licensing rules created since the last review.

There are federalism concerns about the RBI Act. Congress would be nudging states towards certain behavior with the carrot of immunity from antitrust lawsuit. Sarah Allen, a deputy attorney general in Virginia, said Tuesday that many states might be unwilling to make the changes suggested by Issa's bill, and would perhaps rather "take their chances" in court against potential anti-trust lawsuits like the one brought against the dental board in North Carolina.

The real problem, says Allensworth, is the regulatory infrastructure that has built up over the decades. There's almost unanimous, bipartisan agreement that licensing reform must be undertaken—good luck finding many other issues where Issa agrees with something the Obama administration said—yet the number of licensing laws continues to grow and more workers than ever before must get a government-issues permission slip before going to work.

The RBI act would make licensing regulations a function of the state government, the way they should be, Allensworth said, though she had a mixed opinion of some of the bill's provisions—including one element that would make it easier for workers and businesses to take licensing boards to court over disagreements.

"I want the state to take governmental responsibility for the regulation they create," she says. "Once states know the lay of the land, they will be able to balance the competitive costs of regulations themselves."

APPENDIX L:

The Truth About Dentistry

Itʼs much less scientific—and more prone to gratuitous procedures—than you may think.

FERRIS JABR

MAY 2019 ISSUE | HEALTH

Arsh Raziuddin

Like The Atlantic's family coverage? Subscribe to The Family Weekly, our free newsletter delivered to your inbox every Saturday morning.

Email SIGN UP

I N THE EARLY 2000S Terry Mitchell’s dentist retired. For a while, Mitchell, an electrician in his 50s, stopped seeking dental care altogether. But when one of his wisdom teeth began to ache, he started looking for someone new. An

acquaintance recommended John Roger Lund, whose practice was a convenient 10-minute walk from Mitchell’s home, in San Jose, California. Lund’s practice was situated in a one-story building with clay roof tiles that housed several dental offices. The interior was a little dated, but not dingy. The waiting room was small

and the decor minimal: some plants and photos, no fish. Lund was a good- looking middle-aged guy with arched eyebrows, round glasses, and graying hair that framed a youthful face. He was charming, chatty, and upbeat. At the time, Mitchell and Lund both owned Chevrolet Chevelles, and they bonded over their mutual love of classic cars.

Lund extracted the wisdom tooth with no complications, and Mitchell began seeing him regularly. He never had any pain or new complaints, but Lund encouraged many additional treatments nonetheless. A typical person might get one or two root canals in a lifetime. In the space of seven years, Lund gave Mitchell nine root canals and just as many crowns. Mitchell’s insurance covered only a small portion of each procedure, so he paid a total of about $50,000 out of pocket. The number and cost of the treatments did not trouble him. He had no idea that it was unusual to undergo so many root canals—he thought they were just as common as fillings. The payments were spread out over a relatively long period of time. And he trusted Lund completely. He figured that if he needed the treatments, then he might as well get them before things grew worse.

Meanwhile, another of Lund’s patients was going through a similar experience. Joyce Cordi, a businesswoman in her 50s, had learned of Lund through 1-800- DENTIST. She remembers the service giving him an excellent rating. When she visited Lund for the first time, in 1999, she had never had so much as a cavity. To the best of her knowledge her teeth were perfectly healthy, although she’d had a small dental bridge installed to fix a rare congenital anomaly (she was born with one tooth trapped inside another and had had them extracted). Within a year, Lund was questioning the resilience of her bridge and telling her she needed root canals and crowns.

TheAtlantic – The Trouble With Dentistry - The Atlantic - Ferris Jabr

To hear more feature stories, see our full list or get the Audm iPhone app.

Cordi was somewhat perplexed. Why the sudden need for so many procedures after decades of good dental health? When she expressed uncertainty, she says, Lund always had an answer ready. The cavity on this tooth was in the wrong position to treat with a typical filling, he told her on one occasion. Her gums were receding, which had resulted in tooth decay, he explained during another visit. Clearly she had been grinding her teeth. And, after all, she was getting older. As a doctor’s daughter, Cordi had been raised with an especially respectful view of medical professionals. Lund was insistent, so she agreed to the procedures. Over the course of a decade, Lund gave Cordi 10 root canals and 10 crowns. He also chiseled out her bridge, replacing it with two new ones that left a conspicuous gap in her front teeth. Altogether, the work cost her about $70,000.

A masked figure looms over your recumbent body, wielding power tools and sharp metal instruments, doing things to your mouth you cannot see.